|

|

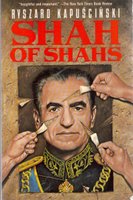

humint

|

|

|

|

|

|

IRANIAN HISTORY - The Dead Flame A nation trampled by despotism, degraded, forced into the role of an object, seeks shelter, seeks a place where it can dig itself in, wall itself off, be itself. This is indispensable if it is to preserve its individuality, its identity, even its ordinariness. But a whole nation cannot emigrate, so it undertakes a migration in time rather than in space. In the face of the encircling afflictions and threats of reality, it goes back to a past that seems a lost paradise. It regains its security in customs so old and therefore so sacred that authority fears to combat them. This is why a gradual rebirth of old customs, beliefs, and symbols occurs under the lid of every dictatorship—in opposition to, against the will of the dictatorship. The old acquires a new sense, a new and provocative meaning. This happens hesitantly and often secretly at first, but as the dictatorship grows increasingly unbearable and oppressive, the strength and scope of the return to the old increase. Some voices call this a regressive return to the middle ages. So it may be. But more often, this is the way the people vent their opposition. Since authority claims to represent progress and modernity, we will show that our values are different. This is more a matter of political spite than a desire to recapture the forgotten world of the ancestors. Only let life get better and the old customs lose their emotional coloration to become again what they were—a ritual form. Such a ritual, suddenly transformed into a political act under the influence of the growing opposition spirit, was the commemoration of the dead forty days after their death. What had been a ceremony of family and neighbors turned into a protest meeting. Forty days after the Qom events, people gathered in the mosques of many Iranian towns to commemorate the victims of the massacre. In Tabriz, the tension grew so high that an insurrection broke out. A crowd marched through the street shouting "Death to the Shah." The army rolled in and drowned the city in blood. Hundreds were killed, thousands were wounded. After forty days, the towns went into mourning—-it was time to commemorate the Tabriz massacre. In one town—Isfahan—a despairing, angry crowd welled into the streets. The army surrounded the demonstrators and opened fire; more people died. Another forty days pass and mourning crowds now assemble in dozens of towns to commemorate those who fell in Isfahan. There are more demonstrations and massacres. Forty days later, the same thing repeats itself in Meshed. Next it happens in Teheran, and then in Teheran again. In the end it is happening in nearly every city and town. Thus the Iranian revolution develops in a rhythm of explosions succeeding each other at forty-day intervals. Every forty days there is an explosion of despair, anger, blood. Each time the explosion is more horrible—bigger and bigger crowds, more and more victims. The mechanism of terror begins to run in reverse. Terror is used in order to terrify. But now, the terror that the authorities apply serves to excite the nation to new struggles and new assaults. The Shah's reflex was typical of all despots: Strike first and suppress, then think it over: What next? First display muscle, make a show of strength, and later perhaps demonstrate you also have a brain. Despotic authority attaches great importance to being considered strong, and much less to being admired for its wisdom. Besides, what does wisdom mean to a despot? It means skill in the use of power. The wise despot knows when and how to strike. This continual display of power is necessary because, at root, any dictatorship appeals to the lowest instincts of the governed: fear, aggressiveness toward one's neighbors, bootlicking. Terror most effectively excites such instincts, and fear of strength is the wellspring of terror. A despot believes that man is an abject creature. Abject people fill his court and populate his environment. A terrorized society will behave like an unthinking, submissive mob for a long time. Feeding it is enough to make it obey. Provided with amusements, it's happy. The rather small arsenal of political tricks has not changed in millennia. Thus, we have all the amateurs in politics, all the ones convinced they would know how to govern if only they had the authority. Yet surprising things can also happen. Here is a well-fed and well-entertained crowd that stops obeying. It begins to demand something more than entertainment. It wants freedom, it demands justice. The despot is stunned. He doesn't know how to see a man in all his fullness and glory. In the end such a man threatens dictatorship, he is its enemy. So it gathers its strength to destroy him. Although dictatorship despises the people, it takes pains to win their recognition. In spite of being lawless—or rather, because it is lawless—it strives for the appearance of legality. On this point it is exceedingly touchy, morbidly oversensitive. Moreover, it suffers from a feeling (however deeply hidden) of inferiority. So it spares no pains to demonstrate to itself and others the popular approval it enjoys. Even if this support is a mere charade, it feels satisfying. So what if it's only an appearance? The world of dictatorship is full of appearances. The Shah, too, felt the need of approval. Accordingly, when the last victims of the TabrizTabriz for the occasion. massacre had been buried, a demonstration of support for the monarchy was organized in that city. Activists of the Shah's party, Ras-takhiz, were assembled on the great town commons. They carried portraits of their leader with suns painted above his monarchical head. The whole government appeared on the reviewing stand. Prime Minister Jamshid Amuzegar addressed the gathering. The speaker wondered how a few anarchists and nihilists could destroy the nation's unity and upset its tranquility. "They are so few that it is even hard to speak of a group. This is a handful of people." Fortunately, he said, words of condemnation were flowing in from all over the country against those who want to ruin our homes and our well-being—after which a resolution of support for the Shah was passed. When the demonstration ended, the participants sneaked home. Most were carried by buses to the nearby towns from which they'd been imported to After this demonstration, the Shah felt better. He seemed to be getting back on his feet. Until then he had been playing with cards marked with blood. Now he made up his mind to play with a clean deck. To gain popular sympathy, he dismissed a few of the officers who had been in charge of the units that opened fire on the inhabitants of Tabriz. Among the generals, this move caused murmurs of discontent. To appease the generals, he ordered that the inhabitants of Isfahan be fired on. The people responded with an outburst of anger and hatred. He wanted to appease the people, so he dismissed the head of Savak. Savak was appalled. To appease Savak, the Shah allowed them to arrest whomever they wished. And so by reversals, detours, meander-ings, and zig-zags, step by step, he drew nearer to the precipice. The Shah was reproached for being irresolute. Politicians, they say, ought to be resolute. But resolute about what? The Shah was resolute about retaining his throne, and to this end he explored every possibility. He tried shooting and he tried democratizing, he locked people up and he released them, he fired some and promoted others, he threatened and then he commended. All in vain. People simply did not want a Shah anymore; they did not want that kind of authority. The Shah's vanity did him in. He thought of himself as the father of his country, but the country rose against him. He took it to heart and felt it keenly. At any price (unfortunately, even blood) he wanted to restore the former image, cherished for years, of a happy people prostrate in gratitude before their benefactor. But he forgot that we are living in times when people demand rights, not grace. He also may have perished because he took himself too literally, too seriously. He certainly believed that the people worshipped him and thought of him as the best and worthiest part of themselves, the highest good. The sight of their revolt was inconceivable, shocking, too much for his nerves. He reckoned he had to react immediately. This led him to violent, hysterical, mad decisions. He lacked a certain dose of cynicism. He could have said: "They're demonstrating? So let them demonstrate. Half a year? A year? I can wait it out. In any case, I won't budge from the palace." And the people, disenchanted and embittered, willy-nilly, would have gone home in the end because it's unreasonable to expect people to spend their whole lives marching in demonstrations. But the Shah didn't want to wait. And in politics you have to know how to wait. He also perished because he did not know his own country. He spent his whole life in the palace. When he would leave the palace, he would do it like someone sticking his head out the door of a warm room into the freezing cold. Look around a minute and duck back in! Yet the same structure of destructive and deforming laws operates in the life of all palaces. So it has been from time immemorial, so it is and shall be. You can build ten new palaces, but as soon as they are finished they become subject to the same laws that existed in the palaces built five thousand years ago. The only solution is to treat the palace as a temporary abode, the same way you treat a streetcar or a bus. You get on, ride a while, and then get off. And it's very good to remember to get off at the right stop and not ride too far. The most difficult thing to do while living in a palace is to imagine a different life—for instance, your own life, but outside of and minus the palace. Toward the end, the ruler finds people willing to help him out. Many lives, regrettably, can be lost at such moments. The problem of honor in politics. Take de Gaulle—a man of honor. He lost a referendum, tidied up his desk, and left the palace, never to return. He wanted to govern only under the condition that the majority accept him. The moment the majority refused him their trust, he left. But how many are like him? The others will cry, but they won't move; they'll torment the nation, but they won't budge. Thrown out one door, they sneak in through another; kicked down the stairs, they begin to crawl back up. They will excuse themselves, bow and scrape, lie and simper, provided they can stay—or provided they can return. They will hold out their hands—Look, no blood on them. But the very fact of having to show those hands covers them with the deepest shame. They will turn their pockets inside out—Look, there's not much there. But the very fact of exposing their pockets—how humiliat-.ing! The Shah, when he left the palace, was crying. At the airport he was crying again. Later he explained in interviews how much money he had, and that it was less than people thought. I spent whole days roaming around Teheran with no purpose or end in mind. I was escaping from the wearisome emptiness of my room and from my aggressive, slanderous hag of a cleaning woman. She was always asking for money. She took my clean, pressed shirts when they came back from the laundry, dunked them in water, strung them on a line—and demanded payment. For what? For ruining my shirts? Her scrawny claw was always thrust out from beneath her chador. I knew she had no money. But neither had I. This was something she couldn't understand. A man from the outside world is by definition rich. The hotel owner shrugged her shoulders—"I can't do anything about it. As a result of the revolution, my dear sir, that woman now has power." The hotel owner treated me as a natural ally, a counterrevolutionary. She assumed that my views were liberal; liberals, as people of the center, were at that time under the sharpest attack. Choose between God and Satan! Official propaganda expected a clear declaration from everyone; the time of the purges and of what they called "examining each other's hands" had begun. |